The nineteenth century was a time of great change in the churches of Britain and the United States. This period witnessed an explosion of worldwide missions as William Carey, Adoniram Judson, Henry Martyn, Hudson Taylor, and many others led waves of Protestant missionaries to fields around the world. At the same time, churches came under attack both from the challenge of new cults and sects, and from the philosophical acids of Darwinism and German Higher Criticism. In the midst of these remarkable events, God raised up a stream of faithful men who preached Reformed doctrine to the heart worked by the Holy Spirit in the soul. One of the greatest of these preachers was Archibald Alexander. After briefly summarizing his life and ministry in this article, I will focus on how he typically preached Spirit-worked faith in contrast to dead faith in one of his sermons. Such discriminatory preaching is all too rare today.

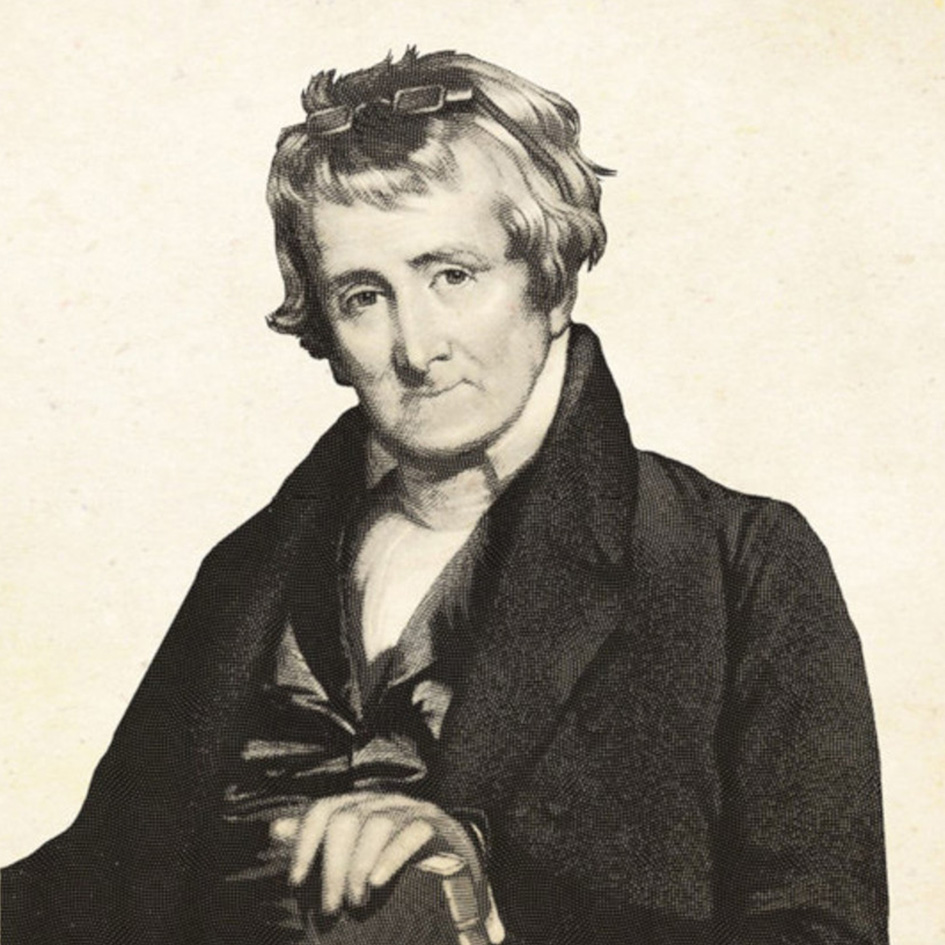

Archibald Alexander (1772–1851): Life and Ministry

Archibald Alexander was born on April 17, 1772, near Lexington, Virginia. 1On Archibald Alexander, see James W. Alexander, Life of Archibald Alexander (New York: Scribner, 1854); David B. Calhoun, Princeton Seminary (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 1994); Stephen Clark, “Archibald Alexander: The Shakespeare of the Christian Heart,” in The Voice of God (London: Westminster Conference, 2003), 103–20; James M. Garretson, Princeton and Preaching: Archibald Alexander and the Christian Ministry (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 2005); James M. Garretson, ed., Princeton and the Work of the Christian Ministry, 2 vols. (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 2012); Lefferts A. Loetscher, Facing the Enlightenment and Pietism: Archibald Alexander and the Founding of Princeton Theological Seminary (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1983). For a brief introduction to Alexander and his writings on godliness, see “A Scribe Well-Trained”: Archibald Alexander and the Life of Piety, ed. James M. Garretson (Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2011). He grew up as a member of a Scotch-Irish Presbyterian family on the American frontier, living in a log cabin and memorizing the Westminster Shorter Catechism. He was also influenced by the writings of the English Puritan John Flavel. After a prolonged struggle with doubt and conviction of sin, he was converted at age seventeen.

He had already begun studying under William Graham (1745– 1799) at Liberty Hall Academy (now Washington and Lee University). He continued those studies after his conversion with an eye to becoming a minister. Graham passed on to him the theology he had learned from John Witherspoon (1723–1794), president of the College of New Jersey (today’s Princeton University) and the only minister to sign the American Declaration of Independence. Alexander continued to study Puritan writers such as William Bates, Thomas Boston, Jonathan Edwards, and John Owen. After serving as an itinerant evangelist in Virginia and North Carolina, he was ordained as a settled pastor in 1794. In 1796, he became president of Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia while continuing to preach in various churches. He was called to serve as the pastor of the large Pine Street Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia in 1807. There he founded a society for street preaching and evangelistic visitation.

In 1808, he began to call for the founding of a seminary to train Presbyterian ministers. Two years later, he was awarded the doctor of divinity degree by the College of New Jersey. In 1812, the General Assembly appointed him the first professor of the newly instituted Princeton Theological Seminary. He served there for thirty-nine years, mostly as professor of didactic and polemical theology. The small school blossomed and bore much fruit. W. J. Grier writes, “His classes at Princeton grew from nine in the first year until by the time of his death 1,837 young men had sat at his feet.”2W. J. Grier, “Biographical Introduction,” in Archibald Alexander, Thoughts on Religious Experience (London: Banner of Truth, 1967), xiv. His colleagues Charles Hodge (1797–1878) and Samuel Miller (1769–1850) held him in the highest regard. There was a beautiful unity at Princeton, arising from the faculty’s Christlike spirit and common devotion to the truth of the Scriptures. The son of Charles Hodge, Archibald Alexander Hodge (whose very name testifies of his father’s love for Professor Alexander), writes: “I have had a wide experience of professors and of pastors, and I am certain, I have never seen any three who together approached these three in absolute singleness of mind, in simplicity and godly sincerity, in utter unselfishness and devotion to the common cause, each in honor preferring one another. Truth and candor was the atmosphere they breathed, loyalty, brave and sweet, was the spirit of their lives.”3Archibald Alexander Hodge, The Life of Charles Hodge: Professor in the Theological Seminary, Princeton, N.J. (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1880), 378.

Alexander established a pattern for the seminary that combined rigorous biblical studies in the original languages, vibrant preaching in hopes of seeing spiritual revival, faithful adherence to the Reformed theology of the Westminster Standards and Francis Turretin (1623–1687), defense of the truth of the faith with the tools of Scottish Common Sense Realism, and promotion of fervent piety and Christian experience. The original “Design of the Seminary” stated that the school aimed “to unite in those who shall sustain the ministerial office, religion and literature; that piety of the heart, which is the fruit only of the renewing and sanctifying grace of God, with solid learning; believing that religion without learning, or learning without religion, in the ministers of the gospel, must ultimately prove injurious to the church.”4“History of the Seminary,” Princeton Theological Seminary Web site (Princeton, N.J.), http://www.ptsem.edu/index.aspx?menu1_id=2030&menu2_id =2031&id=1264 (accessed April 5, 2012).

Alexander and his colleagues at Princeton Theological Seminary trained men in Reformed theology and engaged in the theological controversies of the day, such as the debate over the “New Divinity” advocated by Charles Finney (1792–1875).5See the articles by Alexander, Hodge, et al. in Princeton Versus the New Divinity: The Meaning of Sin, Grace, Salvation, Revival: Articles from the Princeton Review (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 2001). However, Alexander also wrote books to teach basic Bible truths, to call children to conversion, to provide readings for family devotions, and to illuminate the Christian’s experience of sin and grace—some of which are still being reprinted, read, and cherished today.6Archibald Alexander, A Brief Compendium of Bible Truth, ed. Joel R. Beeke (Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2005); The Way of Salvation: Familiarly Explained in a Conversation Between a Father and His Children (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1839); Evangelical Truth: Practical Sermons for the Christian Home (Birmingham, Ala.: Solid Ground Christian Books, 2004); Thoughts on Religious Experience. James Garretson writes, “Alexander labored relentlessly to impress the importance of the presence and practice of piety on the generation in which he lived.”7Garretson, introduction to Alexander, “A Scribe Well-Trained,” 25.

In the promotion of piety in the church, Alexander plowed, planted, cultivated, and harvested the fields of God with the tool of preaching. He was known for the priority he gave to sermon preparation and for his effective simplicity of style. He taught his seminary students to avoid “historical, philosophical, or political discussions,” and instead to preach through the “whole system of theology,” especially the “greatest truths,” our moral “duties,” “Christian experience, afflictions and temptations,” and answers for “awakened souls”—all with an emphasis on the Holy Spirit and His saving work. For Alexander, this meant that the preacher must proclaim God’s Word in a discriminatory fashion, distinguishing the Spirit’s saving work by stressing what saving faith is from a dead faith that lacks the saving fruit of the Spirit’s imprint.8Loetscher, Facing the Enlightenment and Pietism, 237–38.

To get a taste of Alexander’s emphasis on discriminatory, Spiritbased preaching, we will look at a sermon that he delivered in April 1791 before the Presbytery of Lexington, Virginia, to obtain his license to preach.9The manuscript of the sermon is in the collections at Princeton Theological Seminary. It has been published as Archibald Alexander, “A Treatise in Which the Difference Between a Living and a Dead Faith Is Explained, 1791,” Banner of Truth, no. 335–336 (Sept. 1991): 39–54. It also appeared in the Banner of Sovereign Grace Truth 2, no. 6 (July/Aug. 1994): 145; vol. 2, no. 7 (Sept. 1994): 181–82; vol. 2, no. 8 (Oct. 1994): 204–6. Though it was preached very early in his career, later in life he recalled, “The view taken of the subject is not materially different from that which I should now take.”10Alexander, Life of Archibald Alexander, 110.

Archibald Alexander Preaching on Spirit-Worked Faith Versus Dead Faith

Excerpt from

PURITAN REFORMED JOURNAL

Volume 12, Number 2 • July 2020

By Joel Beeke